When it comes to close reading, people are my subject. Literature comes second, then paintings and conceptual films like the brief encounters of Cyprien Gaillard, Anna Mendieta, and Kimsooja. I take beauty in doses, in and around human tasks. I have wished to be an aesthete who devours unstoppably. But my friends with this gift tend toward bulimic flaws—a largesse that neither their constitutions nor their bank accounts can sustain—and I don’t.

I tend toward ascetic flaws, to bourgeois preoccupations with bedtimes and meals, a kind of tidy housewifery that hinges on the body’s clockwork. I can read a book a week, perhaps two if they’re worth skimming. But anything more than this and my brain brims with a kind of cognitive indigestion and a humming fear that the pantry is emptying and the closet’s wreck is teetering.

These flaws bear the stamp of my Midwestern female forbears: all assiduous cleaners and forthright cooks, good with budgets, gardens, and crying children. They are women who taught me to mete out beauty in and around work: to hoard Jane Austen novels for an hour before bed, to get up in the early dark to read pencil-and-ink-glossed Psalms. They taught me, too, to buy these hours from men, who, in the family economy, ostensibly owned time. It was an exchange that spurred some women to shrewishness and others to silence.

Literature lured me to look for other glimpses of men, women, their bonds, and infidelities. Male narrators intrigued me, and John Updike’s narrators, in particular, caught me. Updike’s short fiction was a staple of nineties high school and college anthologies, and his parade of husbands and fathers—with their unironic assent to a WASP-y architecture of virginity, marriage, children, and church—made sense to my teenage Southern Baptist self.

I think of the young husband of “Wife-Wooing”: doting on his seven-years’ wife as they sit “on warm broad floorboards, before a fire, the children between us, in a crescent, eating.” It’s a romantic family tableau bronzed by Updike’s gorgeous sentences, the young husband praising his wife’s beauty before veering to bawdiness and a good-natured lampooning of his own quest to win dinner “from the raw hands of the hamburger girl in the diner a mile away.”

And it’s all a sweet set-up: he wants to make love to his wife. The famously brief story charts his designs over the course of twenty-four hours, with only three late paragraphs veering into Updike’s standard disdain for domestically spent women, whose “every wrinkle and sickly tint” register as “a relief and a revenge.” I can imagine myself at fourteen or fifteen, riding the wave of this flirtatious story, then hitting that pass: quizzical, unsure if the authorial hand meant me to understand the narrator’s mocking turn as a masculine lapse or a victory—even as I attempted, in parallel, to discern what logic (loving or mercenary?) drove the terms of headship in my own family.

Those three paragraphs were a foreshadowing of what I would find in Updike’s fictional world: intractable male faithlessness, sometimes laughably lascivious male gazes, and an almost vicious condescension toward women, who seemed to circulate in a child-accessorized pool of first wives, second wives, and lovers. His narrators may veer toward remorse, as when the aging, adulterous narrator of “When Everyone Was Pregnant” compares himself to blinded Gloucester, pitied by the child he betrayed. But their largely happy decadence finally convinced me to agree with David Foster Wallace, who famously declared Updike one of postwar fiction’s Great Male Narcissists.

Oddly, I returned to Updike this winter. I am engaged to marry a man who lives in a town an hour from my city home, and on a long highway drive I caught the cadences of an Updike story in an old New Yorker fiction podcast. So I listened to every recorded narration of his short stories that I could find—”A&P,” “Twin Beds in Rome,” “The Other Side of the Street”—and at the public library in my soon-to-be new hometown, the first books I checked out were voluminous Updike short fiction anthologies.

Rereading his work, I found all the familiar set pieces: the virgin wives, the fiery pearls of phrasing, the quavering logic of married men who slouch victoriously into a lover’s arms. As much as my teenage self never imagined I would make a life on Updike’s East Coast, so I never imagined that in mid-life I would return to him and mark the parallels between his doomed families and my own, collapsed under the weight of debunked headships and infidelities.

Unexpectedly, “Separating” redeemed Updike for me. The afternoon I paged through the crackling, plastic-girded library anthologies, I stumbled on this popular Updike piece known for rounding out the denouement of Richard and Joan Maples’ marriage. I knew bits of the story despite the fact that I had never read it. But even after sinking into its startling sweep, I did not immediately realize that it is a sober bookend to “Wife-Wooing.”

Here, the young husband has become a philanderer primed for his second marriage, and the young mother a brittle, resigned wife. They strike a truce as to how they will tell their children—the infant and toddlers of that warm fireside crescent—that they are separating.

Richard weeps through the speech, citing hay fever, his children trying to ignore the tears that become “a shield for himself against these… innocents, at a table where he sat the last time as head.” Their girls respond coolly to the news. The younger boy gets drunk, eats a cigarette and bursts into proxy tears about a school he hates. The older boy, Richard, Jr., assents quietly, but as his father tucks him into bed, he turns and gives Richard a kiss “on the lips, passionate as a woman’s,” and moans “one word, the crucial, intelligent word: ‘Why?’”

Why. It was a whistle of wind in a crack, a knife thrust, a window thrown open on emptiness. The white face was gone, the darkness was featureless. Richard had forgotten why.

The story’s silent final sentence braided up into the memory of my own family’s revelatory final days: the blustery appeals to happiness and loud, laughably mutual accusations of insanity. Did we ever get to this moment, an unlikely redemption of an intractable narcissist: the true question asked and echoed, the child and parent yoked for a moment in the costliness of cleaving?

Laura Bramon is a writer and international development practitioner based in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in The Best Creative Non-Fiction, Vol. 3 (W.W. Norton), Image, University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, First Thingsonline, Humanum Review, and other outlets.

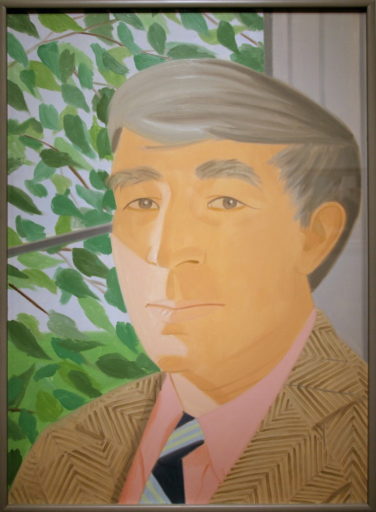

Portrait of Updike: “John Updike” by cliff1066™ is licensed under CC BY 2.0