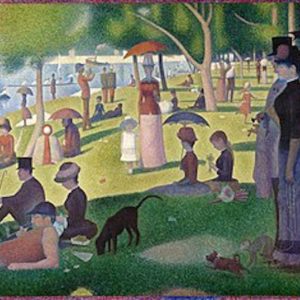

We arrive at the beach house in the dark, the ocean’s roar schooning over the dunes to meet us on the gravel path and ask: who are you? We get out of the car numb from the road and the nerves of a long drive just before the lockdown’s official lift, and we don’t answer. We have no ruse or good excuse for who we are or why we are here, just the common fatigue of pandemic house arrest: one of us sheltering alone, two of us sheltering with children, all three of us swiftly merged in spirit as life quieted, emptied, and closed in like the memory of a Giorgio Morandi still life: a few pieces set together, plain-faced, casting the quick shadows of interior light.

We get our bags and go into a little cottage that smells of salt and damp. The linoleum floor in the kitchen juts like a collapsed tent and upstairs, I lie down on a sway-backed twin bed made with soft old cotton sheets. I can hear the ocean hushed behind the window at my head, so I turn over and thrust up the sash. I find a Saul Bellow book on the cluttered bookcase but I fall asleep with my Bible in my hands, splayed open to the Psalms, listening to one of you stir on the other side of the wall and thinking of “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” the Hopkins poem I read aloud on the long drive up:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same: Deals out that being indoors each one dwells, Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells, Crying What I do is me: for that I came.

The relief of a spare still life is the ease of seeing each thing: the bowl, the cup, the fluted vase. The two of you are at my side as soon as I wake, and we wrap up in thin coats and walk out in bare feet, up the gravel road to the dunes and the gray sea. What is more remarkable: the freedom to walk to the water or the freedom to see your faces, to make real and loud a murmured flood of texts shared as the world shut down? It’s been so long since I saw and heard you speak that it’s strange to count the live beats of your humor and watch you laugh, to hear my voice meet yours.

On Pentecost Eve it’s warm enough to set out beach chairs and blankets and burn our thighs and noses in the sun. We sit in close configuration, shadows brief, a little theater of pieces mutually chosen: as if Morandi’s cups and pitchers sought each other in his silent flat. I watch you both with the eyes of a child who regards the nearest bodies as a map and key for all and a clue to my own, too, and I read again from the little Hopkins book: the same poem, so well-loved that the lines run off my lips like a nursery rhyme: the kingfishers, dragonflies, roundy wells, “each hung bell’s / Bow swung” like a tongue to “fling out broad its name.”

Your names are what I fling out as we talk and stare and laugh, suddenly recalling the old astonishment-at-first-sight stories of how we all met—the way you tell them to a lover or a child: I remember your gauzy red hair, the funny shot of vinegar you sipped, our walk through a warm city neither of us knew; I remember your dark head, the lace of your black dress, the mystery of the midnight party you were headed to alone. And you remember me too.

Now we sit stark against the blue sky, as real as the strange seclusion to which life fitted itself so suddenly. To become small and quiet and solitary so quickly, to lose your daily presence so easily, was a fast poverty that, when we go home, will come again. The poor will always be with you, God says: beloved by Him as equal loves equal, Bernanos says. I feel my feet in the cool, heavy sand and keep the brief sight of you staggered against the sun, lovely in limbs and eyes your own, companionable Christs who search and know me, familiar with all my ways; present or absent, resurrecting me to the Father through the mirrored features of your faces.

Image is Natura Morta, by Giorgio Morandi, courtesy of WikiArt

Laura Bramon is a writer and international development practitioner based in Washington, DC. Her writing has appeared in The Best Creative Non-Fiction, Vol. 3 (W.W. Norton), Image, University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, First Thingsonline, Humanum Review, and other outlets.