My dear L,

The crimp in the line that fed water into our ice maker finally did it. It caused a leak. The man who installed the refrigerator five years ago warned us this could happen. Our kitchen is above our basement. The backed-up water collected above the basement ceiling until, like a cloud, it could hold no more and it released bucketsful of water. My wife and I were each lost in our own private digital lives when we were startled by a smacking sound coming from the basement: that dump of water striking tile floor.

Maybe we can blame the city: after a day-long water outage, a surge of water when the repair was finished couldn’t make it through the crimped line. Maybe we can blame ourselves for allowing the installer to hook up a line he knew would fail.

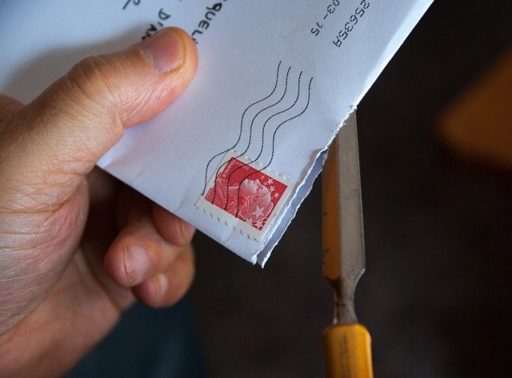

I’m not in the mood to blame. The damage from the flood—40 years’ worth of paperback books, dozens of heavy boxes of papers—brought you back to me. In a 9 x 12 envelope labeled “correspondence to respond to,” eight passionate letters from you. In one you write, “Why don’t you get off your flat ass and drop me a line?” Well, I’m getting back to you now, 35 years later. Too late, as it turns out.

Last week, my wife and I took a chance. We went out of town for a few days. Isle of Palms, South Carolina. Our first outing in seven months. We left on the day when we were supposed to arrive in Madrid to begin a three-week trip to Spain and Portugal to celebrate our 30th anniversary. I was supposed to be retired from work I’ve loved for 30 years: teaching. Covid changed our plans.

Anxiety is the unwelcome guest that shows up too often and refuses to leave. It shuts me down. It made me irritable the morning we loaded the car for the 4 ½ hour drive east from the mountains to the beach, a place we both love. It silenced and distanced me from my wife on our first long walk on the sand. My first immersion in the healing salt water, my own version of a mikvah, started to unlock me. In “Letter to Kizer from Seattle,” poet Richard Hugo writes, “I’m back at the primal source of poems: wind, sea/and rain…” I was back at my primal source, but it would take a day of prayer to open fully to it.

Yom Kippur at the beach. Heavy rain most of the day. We fasted. We prayed with rabbis, cantors, and musicians live-streamed from a synagogue in New York that we love. Thank you, Covid. The music and singing—Mizrahi, Sephardic, and Ashkenazic melodies, an oud, a Middle Eastern drum—the words of the prayers, the tender seriousness, depth and wisdom of the rabbis when they reflected, from time to time, on the meanings of the Day of Atonement: they softened my heart.

That did the trick. My heart now open, the conversations on our long beach walks were rich. My daily immersions in the ocean were purifying. As if with new eyes, I observed pelicans, their muscular wings powering them through the sky, and I felt their strength, their glide. As if for the first time, I saw clouds, nothing written on them, no human markings, no alphabet, no alef bet. The rabbis teach that God created language, the alef bet, first. Then God arranged those letters to form words. And from those words, poof!, the world. Barukh sh’omar v’haya ha’olam. Blessed is the one who spoke and in that instant the world was. God’s in the words, not the world, the rabbis teach. Don’t look up from the sacred text to marvel at the sky, the whitecaps in the distance, the vigilant gull waiting for you to drop a crumb of your sandwich. But keeping our heads in a book, the book: That’s where the trouble begins. That’s where we lose touch with this world, the only world we have.

“The only person that I ever touch,” you write, “left town for a few weeks, and the city [L.A.] feels more threatening than ever…. There must be more to life than writing letters. Trying to describe with words what can only be communicated by touch.” That was in the 1980s, the last time we were in touch. Ours was, for me, a unique relationship. You write, “I miss crossing that fine line between friendship and intimacy with you, like there are no words to describe.”

There are almost no words to describe the nightmare we are living through right now. “[T]hey’re having a vital election here.” That’s Hugo in the same letter poem from the 1970s.

Save the market? Tear it down? The forces of evil maintain they’re trying to save it too, obscuring, of course, the issue. The forces of righteousness, me and my friends, are praying for a storm, one of those grim dark rolling southwest downpours that will leave the electorate sane.

We are having a vital election here, too. The stakes are higher. I’m not hopeful that our electorate will ever be sane again. But you know that, or, knew it. Or maybe you didn’t.

“In 2001 she was driving with her two young children on Rt. 295 when she had a massive brain aneurysm and somehow got her kids home before collapsing. Two days later another aneurysm ruptured. It can’t be explained in any other way than miraculous that she was back at work as a psych nurse six months later.” She: you. I learned this from your obituary. “Madeline passed away peacefully with her family at home after a long illness. We were blessed to have her for nineteen bonus years.” (That is, the nineteen years since her aneurysms.)

October 3rd. After I tossed your letters, I searched for you. You passed away on August 12, less than two months earlier. I retrieved your letters from the recycle bin.

From a log-cabin on East Street in the backwoods of South Thomaston, Maine, where you were living with a bulimic female alcoholic who had pictures of nude men all over her bedroom walls and an obese recovering alcoholic who wished the photos were of him, you write, “Wish you were here almost as often as the fog horn sounds.” I wish I had been there.

Hugo was the first poet I heard read. Well, he didn’t read. He leaned over the lectern and, without a piece of paper or book in front of him, he said his poems to us. To me. They hit me like the most life-giving words in the world.

Your letters: the same. They touch me, your words. My reply? Here I am. I’m writing back. What you said to me, I say to you: “I miss you and love you and wish you were sitting as close to me as the end of this sentence.” Please write back.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com