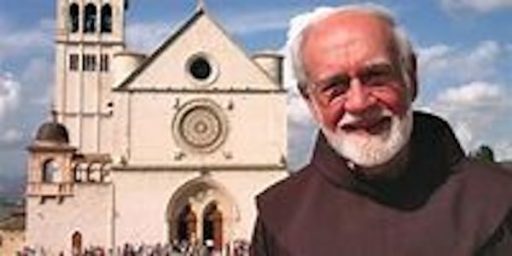

If I listed the titles of all the books that Franciscan priest Murray Bodo has written, I’d use up nearly all of the space that we allow for these Close Reading posts.

At first Bodo’s subject was St. Francis, drawing on his Franciscan heritage and on his personal experience of Assisi, where he led pilgrimages for over forty years. Then St. Clare joined in, then books on spirituality, mystics, a memoir, and more. As his prose books continued, Bodo soon began writing poems—collected in nine previous volumes.

Now, in his latest volume of poetry—Teaching the Soul to Speak—he is saying some goodbyes. Bodo is in his eighties, as he mentions in several of the poems. His yearly pilgrimages to Assisi are apparently over, but the city and all that it has meant to him stay alive in his poems, filling here an entire section of the book. This section’s title is “Homeward Bound,” and I love how these words reverberate with multiple referents. In one poem (“Feet”), he calls Assisi his “second home.” But, as some of the poems dramatize, he has left Assisi perhaps forever, so he’s heading homeward to America. Finally, with many of these poems reflecting on old age and death, the home he is bound for could be heaven.

Given Bodo’s age, it’s natural that many poems in this volume muse on being in the final phase of his life. And on memory—which someone in his eighties has plenty of. Often, though, he evokes memory only to reject living primarily in the past:

What he didn’t want

was all memory

He had seen it in others

when they wrote the late poems

what made the memories

More of it and maybe new

No old dog but a puppy (“Seeing Again”)

Similarly, his short poem “The Poem” names “remembering” only to reject it:

It’s not the remembering

mainly but discovering

and it’s not about thinking

so much as the surprise of

feeling the words connect on

the empty indifferent page

I enjoy here how the gerunds—remembering, discovering, thinking, feeling—enact the writing of poetry as a process necessarily in the present.

Yes, the present is very much alive for Bodo. Take the volume’s title poem, “Teaching the Soul to Speak”:

It’s words does it, teach the soul

to speak so it becomes song.

How, though, and what lexicon

of assonance and sibilants

to speak the sound of the soul?

Seems it’s something beyond self

that gives the soul notes and clef

and a rhythm like the earth’s

spin in spinning galaxies

Or simply the heart in

and out of its own rhythm,

a singable human song

of body, the soul’s portal.

The vision here is fascinating. To speak, the soul is entirely dependent on the body: the body’s words, natural rhythms, and—especially—song. In fact, the soul only truly speaks when “it becomes song.”

Singing is central to Bodo’s vision in other poems as well. “Still and Jamb” is one of the volume’s rare poems in which memory is seen as positive—because it (like the “soul” in the previous poem) “becomes song.” This singing is, paradoxically, the “fullness” of memory’s “silence”:

So it was I learned that noise

makes silence unnatural

that once was all we could hear

We journey back all our lives

to hear the silence singing

as when the silence returns

not as an emptiness but

fullness that is almost sound

that is already dissolved

memory becoming song

There’s more singing in “GodSong”—

Is it singing that does it

brings me to you the way

melody just happens when

I’m singing whatever comes

to mind and the words find

their own beat and melody?…

And if I’m thinking of you

the words keep going home to

where you are listening for

what I’ll say that I think is

not in me to say until

I find music in the words

It’s not only music that Bodo finds in the words. For in the words of his poems—in the process of writing them—he finds an affirmation of life. In one’s eighties, activities requiring physical stamina are probably over; but as long as the mind stays alert, the poems can keep coming, can even be “life savers.” Here in full is the book’s final poem, “Pilgrim Poet’s Prayer”:

It’s okay, the losses

as long as

poems keep filling

the empty spaces

I fall into

their swimming

syllables

floating life savers

Has it come

that far, then,

sink or swim

in syllables

It’s more likely

dive in or

watch them

swim away

O holy words

stay with me

draw me into

your buoyancy

This final stanza is, for me, the perfect ending to the book. Its two-beat rhythm feels buoyant. And the rhyming of “buoyancy” with “me” enacts what the stanza prays for: the very writing of poetry gives Bodo the ability to stay afloat in what remains of his life.

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values, a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America, The Christian Century, and Image, and in books that can be found here.