Some desire / to possess the whole splendid day.

A day of apple picking. Betsy Sholl’s poem “Apple.”

Lately, my days are broken, lacking splendor. Or maybe I’m broken, unable to perceive the splendor that is, even in these awful days, always there. In 1997, Dylan sang, it’s not dark yet, but it’s gettin’ there. In 2016, Leonard Cohen sang, you want it darker / we kill the flame.

The night before the election. Textbanking for Bend the Arc, an organization of progressive Jews from across the country. Immediately after completing my first batch of 200 texts, the first reply: listen kike i’ll see you bending over in the ovens.

Still, there is splendor, if only in a poem.

Crisp air, press of ladder rung on instep, tree sway and dappled light, then stem twist and the weight of apple in hand—

Light and weight and texture and time live in these lines. And when I’m with the poem, light and weight and texture and time live in me. “Apple” continues:

reaching through that leafy green, did we ask what else we were after? Some desire to possess the whole splendid day, sunglint on grass, September’s slow withdrawal, the drying leaves sparse now, so the apples were little flames.

What’s a “whole” day? Is it just the seconds, minutes, and hours and everything that transpires in a fixed amount of time, one day set apart from another, this day from the next?

Already in my experience of this poem, the whole day includes the present—its language exists only in the present moment of my contact with it—and the past. The apple picking took place sometime in the past—”did we ask / what else we are after”. But the question itself and the response to it—what else were we after? “Some desire”—brings an old story into the poem. You know the one—the story of a garden and a woman and a snake and an apple and a man and a god.

Considering apples, Sholl reflects,

…Strange that we make one fruit both medicine and poison, prescribed and forbidden as if everything’s mixed, and there’s no forgetting that darker hunger at work, blind to the damage it does … But also windfalls in wet grass—paradox of fortune—how sweet for the bees and wasps

An apple: both medicine and poison, both fleshy, edible fruit and symbol. A whole day holds it all: thing and idea, nature and culture, the present, the recent past, the biblical past.

The poem concludes with a personal memory.

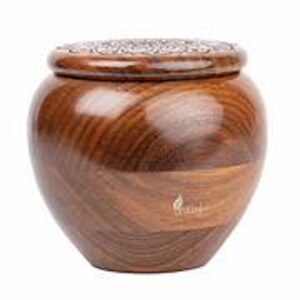

…Once we had a wooden apple made with such skill more than one person picked it up thinking to bite, until our dog finally did. We found it under the couch, splintered and pocked, and with stern voices banished him to the yard—as if once down the stairs he wouldn’t happily enter that bright world of rock and dirt, nuthatch, beetle, squirrel.

Banished, like you know who from the garden. But exile: not a place of toil and suffering. Rather, a bright world. Bright because, in part, here everything is mixed.

But sometimes we refuse to see everything mixed. Sometimes we insist on keeping things and people separate and apart from one another. In Sholl’s poem “On a Line by Charles Wright,” published in the inaugural issue of Pensive: A global journal of spirituality & the arts, she recalls a father’s “black and white world, / his walls and gates to keep everyone in place”.

No walls or gates around Kimberly Avenue down which I drove after an election day morning swim at the Asheville Jewish Community Center. On one side of the street, the historic and luxurious Grove Park Inn. On the other, stately houses and, on the sidewalk, morning walkers. I’ve driven this road daily for thirty-one years. But this time, seeing it through the lens of Sholl’s “On a Line by Charles Wright”—and Baldwin and Morrison and Rankine and Wilkerson and Haydn and so many more—I saw: North Asheville is a white space. Here, nothing is mixed. The walls and gates that keep everyone in place? Neighborhood covenants, urban renewal, redlining, lending practices, generational wealth, school achievement gaps…

One Friday night ten years ago, I was pulled over on peaceful Kimberly Avenue. Earlier that day, my son received the letter he’d been hoping for: he was accepted for admission to the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill! After Shabbat dinner, I dropped him off at a friend’s house and returned home, drunk on joy. I didn’t see the police car in my rearview mirror. When, after I rolled through the stop sign, I saw the flashing blue lights behind me my heart picked up speed. I pulled over, rolled down my window, handed the officer my license and registration. My son was just admitted to college, I told him, hoping for sympathy. Where? Chapel Hill. He looked again at my driver’s license then handed it back to me. It’s a law in North Carolina that all four tires must come to a complete stop at a stop sign. That ended our interaction. Was he a Tar Heel? He didn’t show any sign of team spirit. He was white. I was seen as white. No ticket. No problem. Not once did I fear for my life. Not until recently was I even aware that not once in that encounter with the police did I fear for my life.

“On a Line by Charles Wright” begins,

“God is the fire my feet are held to,” he writes from his yard in Charlottesville and first I picture, not marchers, but my father’s black and white world, his walls and gates to keep everyone in place, going up in smoke and charred soles…

You remember Charlottesville. Lit up at night with tiki torches. Was that a splendid night? Jews will not replace us.

Trump’s final campaign rally was held in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Earlier that day, TRUMP and MAGA were spray-painted in red on headstones in a Jewish cemetery there.

I’m mixed. I’m white, and I’m not.

In “On a Line by Charles Wright,” Sholl asks,

Who decided to call us white, when we are clearly a pale beige version of the rich gleaming dark we came from, watered down…

To the American citizens who marched in Charlottesville, to the American citizens who defaced the Jewish cemetery in Grand Rapids, to the American citizen who hopes to see me in an oven, I say this: I’m trying to hold it all, hope and fear, present and past, apple and fire, light and gleaming dark, exile and home. Read poems. Read Betsy Sholl. Maybe you’ll get lucky, like I did, and get to see the world—your world, my world, our bright, mixed world—more clearly through her eyes, even if just for a moment. May you have the great fortune of finding, through a poem, a world in which we all can live.

Richard Chess directed the Center for Jewish Studies at UNC Asheville for 30 years. He helps lead UNC Asheville’s contemplative inquiry initiative. He is a board member for the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society. He’s published four books of poetry, the most recent of which is Love Nailed to the Doorpost. You can find him at http://www.richardchess.com