Living Traditions

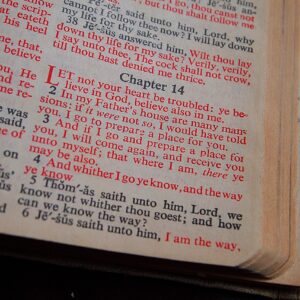

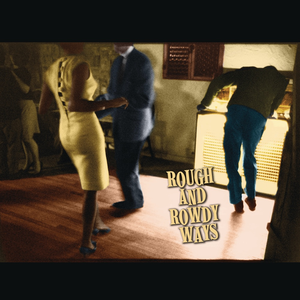

It’s not a good time for “organized religion.” “Nones” now comprise the largest single group in the American religious landscape. The dominant narrative seems less one of accelerating secularization than growing disillusionment with institutions and the communal practices they sustain. All the more interesting, then, when thoughtful writers breathe new life into ancient traditions of prayer, learning, and discipline. Two talented poets—one already well-known; another who soon will be—have new books that go against the contemporary grain.