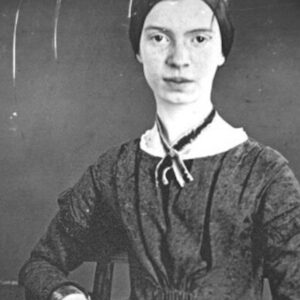

Day One: Close Reading Dickinson

Students know lots of poems—songs from Disney films, lyrics written by Taylor Swift and other popular composers and performers, songs from Broadway musicals, hymns sung at church, Beatles tunes, rap and hip-hop…. But that’s not the same thing as the poetry that students are assigned to read and write about in college courses.