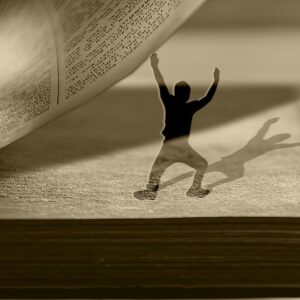

The Most Challenging Book

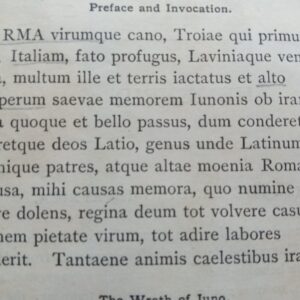

This year, I’ll place my hope in books—history, poetry, Torah, and that most challenging book of all, the book of my life. Everything is in it—good and bad. I’ll try to catch myself when I’m tempted to skim, skip, cut words, sentences, paragraphs, lines, stanzas, pages, entire chapters that challenge and complicate the simple narrative I’d like my days and nights to tell.