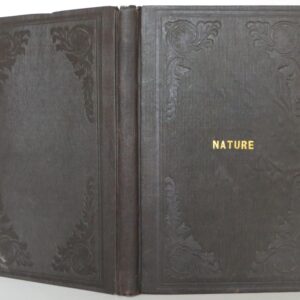

My Mistake: An Example from Emerson

There’s a mistake I sometimes make in my close reading of literature. In the classroom work I’m doing, or in the essay I’m writing, I tend to interpret the words, lines, and sentences at the beginning and the middle from the vantage point of the end. I know where the poem or piece of prose has concluded, and I project what I have come to know into what I had earlier read.