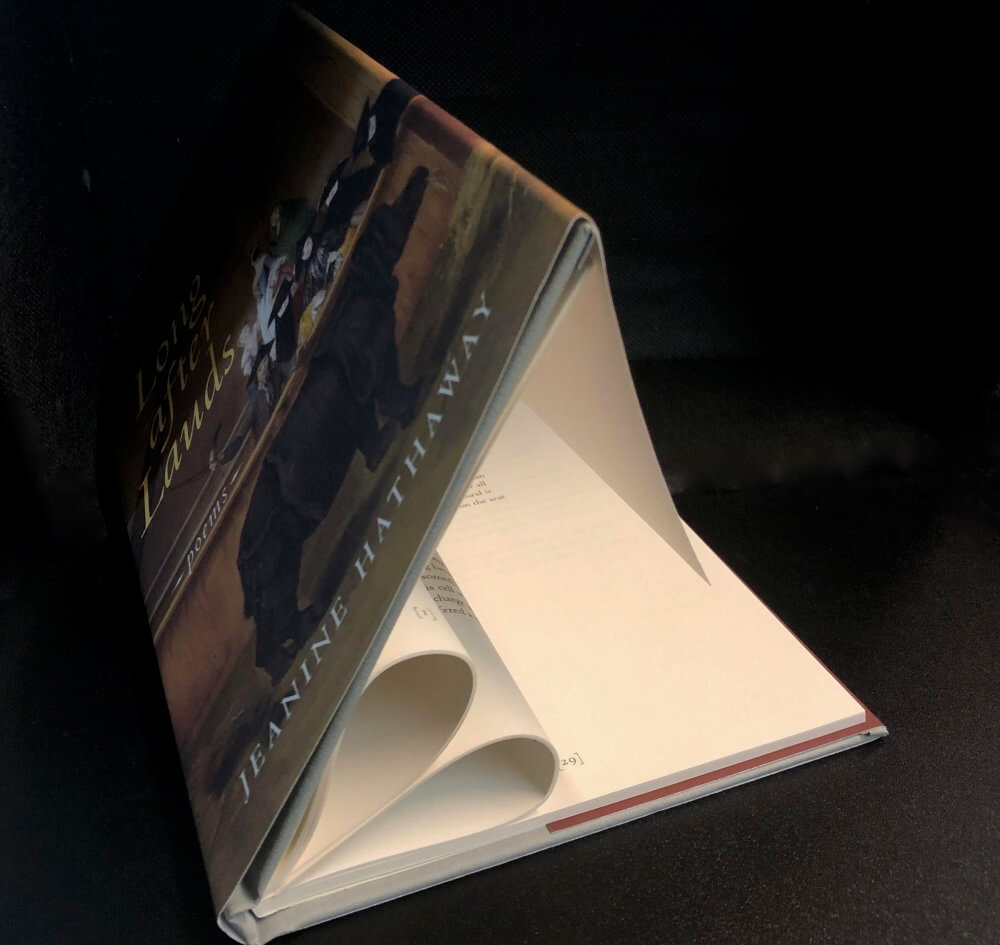

Long after Lauds

Reviewed by Michael Escoubas

While familiarity with Monasticism’s traditional practices of “Matins” and “Lauds” would be helpful in reading Jeanine Hathaway’s new collection, such acquaintance is in no way insisted upon by the author. Indeed, the only requirement needed is the love of excellent poetry. Matins begin during the night, sometimes as early as 2 a.m., and include inspirational readings from the Bible, chanting of psalms and writings from the Church Fathers. These prepare the Community for the next devotional step known as Lauds, or “Praise.” Hathaway writes from the unique perspective of being an “ex-nun.”

This posture gives the poet a wide-ranging view of faith, the church and contemporary life without owing allegiance to conventional expectations. Thus, the title Long after Lauds, encompasses quite nicely the collection’s thrust.

Cover Art

When was the last time you opened a book of poems whose cover art featured a rhinoceros chowing down on a serving of hay with assorted religious figures overlooking the scene? This unique cover, Exhibition of a Rhinoceros at Venice, by Pietro Longhi, (1751), offered this reviewer, a rich source of metaphor and mystery.

Interesting Titles

Who wouldn’t want to explore a collection that showcases captivating titles like, “Ichthyology,” (I had to grab my Merriam-Webster’s), “Biopoiesis,” “Landscape of the Mind,” “Not Quitting Adult Tap,” “At Kroger’s the Day After My Former Husband Died,” and “Saints and Ain’ts.” And these are just for starters. The poetic development of Hathaway’s intriguing titles did not disappoint your reviewer.

Form, Style and Poetic Devices

Hathaway’s poetry does not feature end-rhyme as a major creative tool. However, when she does employ rhyme, her skill is self-evident, as in this excerpt from

“Biopoiesis”

for creative writing students

You wish the ancients’ tricks were so easy still:

Bury a young bull (which first you’ll have to kill).

Be sure his horns poke through, above the ground.

Let pass one month; check back as bees surround

the stinking mush from which they seem to rise. Alive

with fresh direction now, they build a hive,

select their queen, make royal jelly—muse;

they dance in air a map, or perhaps a ruse.

Hathaway’s work uses a variety of stanza combinations: couplets, tercets, and quatrains, to name but a few examples. She writes in a free verse, lyric-rich style, salt and peppered liberally with alliteration, assonance, internal rhyme, sibilance, onomatopoeia and more. Many of these appear in this delightful sestet

“A Long Engagement”

Tickbird sits on Rhino’s ear: trik-quiss, her hiss

and crackling set his very horns on edge. She plucks

and crushes ticks, then sips the opened wound,

beak pressed to blood, blood the better food.

But what symbiosis is utterly benign? Who

wants myth’s arrangement falsified by fact?

The Ex-Nun Poems

In an interview with her publicist, Hathaway was asked about several poems written from the perspective of being an “Ex.” The poet’s reply: “Being an ex is both a prospect and a refuge. How I look at the world now is affected by sensibilities cultivated in former circumstances. X marks the spot where I might discover something important and enriching.” Poetry is Hathaway’s bridge to exploring, growing and discovering.

As I paid careful attention to the Ex-Nun poems profound life-wisdom issued from them. In “The Ex-Nun & the Priest: Questions of Innocence,” Hathaway, recalls walking past Chicago’s Navy Pier with a priest who invited her to have a pastry with him and “watch folks go to work.” The poem poses but does completely resolve hard questions such as, “What is sin”? The whole scene is one in which two people, clergy and secular, struggle with authenticity of faith-profession versus authenticity of faith-practice.

“The Ex-Nun Remembers the Ruler” explores the conundrum of what it means or does not mean to “measure up” in life. You won’t want to skip over Hathaway’s several applications of “ruler” as metaphor

Over metrics she’d chosen the illogical 12

inch to honor the apostles. Considered dividing

the product of 4 x 3 into red-hatted cardinal

directions adjusted by Paul’s theological

virtues. And the greatest of these?

Like a ship elegantly entering its slip along the pier, Hathaway closes out her collection with “Sabbatical: Morning and Comfort.” Here the poet finds herself living in a leased room reflecting “in candlelight’s secular Matins with coffee.” She shares a common wall with her landlady, hears her footsteps as she fills her kettle, the clunk of the latch on her cupboard door, even a perfunctory sneeze. The poet finds in these shared common things “the pad of her socks, the caw of early birds, pages of a newspaper lightly turning” things worthy of praise, Lauds that lift her spirit.

It has been said that the artist is one who feels everything more deeply, the beautiful as well as the terrible, and builds of those feelings shelters where others can safely and sacredly process their own. Jeanine Hathaway is such an artist, Long after Lauds is such a collection.